As you might’ve heard, we had an election this past November.

Perhaps you were living under a rock in a locked container that was hermetically sealed and then buried in the earth’s mantle before going on a top-secret mission to the planet’s core? Yeah, you probably still heard.

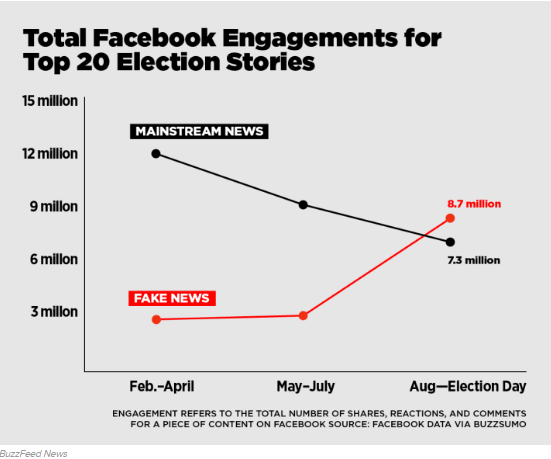

Along with tax returns, email servers and plenty of other subjects, fake news on social media platforms was a much-discussed topic. And like Election Day itself, the implications of fake news on social will reverberate well beyond this election season.

Here’s a cliff notes version, for those who didn’t follow it closely:

There was an enormous amount of misinformation on social platforms about politics in the run-up to the election. A lot of us get political information from social platforms, Facebook in particular. Some people who worked for social networks had serious reservations about their role almost immediately. In the months since Tuesday November 8, Facebook has unveiled new ways to fight fake news, while Twitter introduced tools to mute and report hateful conduct, a longstanding issue on the platform.

How about it, then? Will social media companies, featuring some of the best and brightest, be able to settle for us what’s fake news and what isn’t?

How about it, then? Will social media companies, featuring some of the best and brightest, be able to settle for us what’s fake news and what isn’t?

In a word… nope! Here’s why they are sure to fail, told through one small example.

Among a certain group of people, it’s long been fashionable to declare that certain other people don’t pay any federal income tax. If true, that seems kind of unfair, right? Like they’re getting off easy?

The thing is, they aren’t. The reason that many U.S. workers don’t pay federal income tax is because they don’t make all that much money, and in fact many people who fit that description pay a higher percentage of their income due to local taxes, payroll taxes and the like.

If the above example seems abstract, here’s why it matters. The phrase in question (50% of the people in this country pay no income tax!) is true, but it can give voters exactly the wrong overarching idea (that others who make less have it easier than them).

Would the above be an example of “fake news?” That’s hard to say. A more appropriate term is “technically true, but grossly misleading.”

Most political rhetoric lives in that kind of gray area, because it allows candidates to push their agendas without saying outright falsehoods. This is part of the reason that it has traditionally been tricky to catch a politician lying outright.

How brands can steer clear

From their perspective, large brands should steer clear of this entire debate on social, with a few notable exceptions. Political arguments often bring more heat than light, and that’s especially true when they take place online. Except for brands with a very clear identity that matches their customer base (think Ben & Jerry’s), politics is a high-voltage area and should not be entered lightly.

Most companies with a couple dozen employees or more are probably serving stakeholders of all political ideologies and persuasions. Because of that, even if they think all their customers will agree with a particular statement, putting it out there courts more risk than reward, because in this era, there’s precious little that’s considered consensus across the aisle.

At the end of the day, social networks can’t fix the problem of fake news, because it’s a lot bigger than them. The fake news fight is one more manifestation of America’s political polarization. And solving that problem is well above even Mark Zuckerberg’s paygrade.